What Is An Example Of How Thomas Jeffersonã¢â‚¬â„¢s Political Views Changed After He Became President?

When Thomas Jefferson penned "all men are created equal," he did not mean individual equality, says Stanford scholar

When the Continental Congress adopted the Declaration of Independence on July four, 1776, it was a call for the right to statehood rather than individual liberties, says Stanford historian Jack Rakove. Just subsequently the American Revolution did people interpret it equally a promise for private equality.

By Melissa De Witte

In the decades following the Annunciation of Independence, Americans began reading the affirmation that "all men are created equal" in different ways than the framers intended, says Stanford historian Jack Rakove.

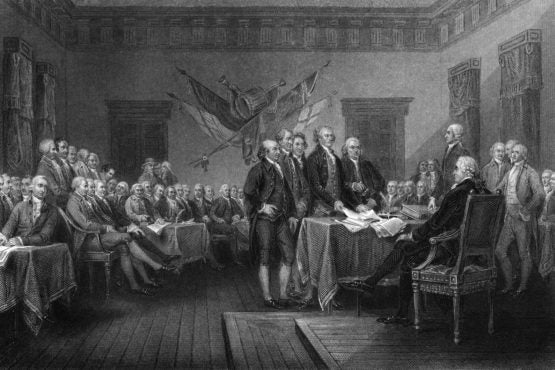

With each generation, the words expressed in the Declaration of Independence have expanded across what the founding fathers originally intended when they adopted the historic certificate on July four, 1776, says Stanford historian Jack Rakove. (Image credit: Getty Images)

On July 4, 1776, when the Continental Congress adopted the historic text drafted by Thomas Jefferson, they did not intend it to mean individual equality. Rather, what they declared was that American colonists, as a people, had the same rights to self-government every bit other nations. Because they possessed this fundamental right, Rakove said, they could establish new governments within each of the states and collectively assume their "separate and equal station" with other nations. Information technology was only in the decades after the American Revolutionary War that the phrase caused its compelling reputation as a statement of individual equality.

Here, Rakove reflects on this history and how now, in a time of heightened scrutiny of the country's founders and the legacy of slavery and racial injustices they perpetuated, Americans can ameliorate understand the limitations and failings of their past governments.

Rakove is the William Robertson Coe Professor of History and American Studies and professor of political scientific discipline, emeritus, in the Schoolhouse of Humanities and Sciences. His book, Original Meanings: Politics and Ideas in the Making of the Constitution (1996), won the Pulitzer Prize in History. His new book, Across Belief, Beyond Conscience: The Radical Significance of the Free Practice of Organized religion will exist published next month.

With the U.S. against its history of systemic racism, are there whatsoever bug that Americans are reckoning with today that can exist traced dorsum to the Announcement of Independence and the U.S. Constitution?

I view the Proclamation equally a betoken of departure and a promise, and the Constitution as a set of commitments that had lasting consequences – some troubling, others transformative. The Declaration, in its remarkable concision, gives us self-axiomatic truths that class the bounds of the correct to revolution and the chapters to create new governments resting on popular consent. The original Constitution, by contrast, involved a set up of political commitments that recognized the legal condition of slavery within the states and made the federal regime partially responsible for upholding "the peculiar institution." As my late colleague Don Fehrenbacher argued, the Constitution was deeply implicated in establishing "a slaveholders' republic" that protected slavery in complex ways downward to 1861.

But the Reconstruction amendments of 1865-1870 marked a 2d constitutional founding that rested on other premises. Together they made a broader definition of equality part of the ramble order, and they gave the national government an effective basis for challenging racial inequalities inside the states. It sadly took far too long for the Second Reconstruction of the 1960s to implement that commitment, but when information technology did, information technology was a fulfillment of the original vision of the 1860s.

Every bit people critically examine the state's founding history, what might they be surprised to acquire from your inquiry that can inform their agreement of American history today?

Two things. First, the toughest question we face in thinking about the nation'south founding pivots on whether the slaveholding South should accept been part of it or not. If you remember it should have been, information technology is difficult to imagine how the framers of the Constitution could have attained that end without making some set of "compromises" accepting the legal existence of slavery. When we talk over the Ramble Convention, we often praise the compromise giving each state an equal vote in the Senate and condemn the Three Fifths Clause allowing the southern states to count their slaves for purposes of political representation. But where the quarrel between large and small states had zilch to practise with the lasting interests of citizens – you lot never vote on the basis of the size of the state in which yous live – slavery was a real and persisting involvement that 1 had to accommodate for the Union to survive.

2nd, the greatest tragedy of American constitutional history was not the failure of the framers to eliminate slavery in 1787. That choice was simply not bachelor to them. The real tragedy was the failure of Reconstruction and the ensuing emergence of Jim Crow segregation in the belatedly 19th century that took many decades to overturn. That was the great constitutional opportunity that Americans failed to grasp, possibly considering four years of Civil War and a decade of the military occupation of the Southward simply wearied Northern public opinion. Even now, if y'all look at issues of voter suppression, we are nonetheless wrestling with its consequences.

You lot debate that in the decades after the Declaration of Independence, Americans began understanding the Announcement of Independence'southward affirmation that "all men are created equal" in a different way than the framers intended. How did the founding fathers view equality? And how did these diverging interpretations emerge?

When Jefferson wrote "all men are created equal" in the preamble to the Announcement, he was not talking nearly individual equality. What he really meant was that the American colonists, equally a people, had the same rights of cocky-government as other peoples, and hence could declare independence, create new governments and presume their "split up and equal station" among other nations. Only after the Revolution succeeded, Americans began reading that famous phrase another way. Information technology now became a statement of private equality that everyone and every member of a deprived group could merits for himself or herself. With each passing generation, our notion of who that statement covers has expanded. It is that hope of equality that has always defined our constitutional creed.

Thomas Jefferson drafted a passage in the Declaration, later struck out past Congress, that blamed the British monarchy for imposing slavery on unwilling American colonists, describing it as "the brutal war against human nature." Why was this passage removed?

At unlike moments, the Virginia colonists had tried to limit the extent of the slave merchandise, but the British crown had blocked those efforts. Simply Virginians also knew that their slave organization was reproducing itself naturally. They could eliminate the slave trade without eliminating slavery. That was non truthful in the West Indies or Brazil.

The deeper reason for the deletion of this passage was that the members of the Continental Congress were morally embarrassed nigh the colonies' willing interest in the arrangement of chattel slavery. To make any merits of this nature would open them to charges of rank hypocrisy that were all-time left unstated.

If the founding fathers, including Thomas Jefferson, thought slavery was morally corrupt, how did they reconcile owning slaves themselves, and how was information technology even so built into American constabulary?

Two arguments offering the bare beginnings of an answer to this complicated question. The first is that the desire to exploit labor was a central feature of most colonizing societies in the Americas, especially those that relied on the exportation of valuable bolt like carbohydrate, tobacco, rice and (much later) cotton fiber. Inexpensive labor in large quantities was the critical cistron that made these bolt profitable, and planters did not care who provided it – the ethnic population, white indentured servants and somewhen African slaves – and so long as they were there to be exploited.

To say that this organisation of exploitation was morally corrupt requires ane to place when moral arguments against slavery began to appear. One likewise has to recognize that there were 2 sources of moral opposition to slavery, and they just emerged after 1750. One came from radical Protestant sects like the Quakers and Baptists, who came to perceive that the exploitation of slaves was inherently sinful. The other came from the revolutionaries who recognized, as Jefferson argued in his Notes on the State of Virginia, that the very act of owning slaves would implant an "unremitting despotism" that would destroy the capacity of slaveowners to act as republican citizens. The moral corruption that Jefferson worried nearly, in other words, was what would happen to slaveowners who would become victims of their ain "boisterous passions."

But the great problem that Jefferson faced – and which many of his modern critics ignore – is that he could not imagine how black and white peoples could ever coexist as gratis citizens in one republic. In that location was, he argued in Query XIV of his Notes, Jefferson argued that there was already too much foul history dividing these peoples. And worse notwithstanding, Jefferson hypothesized, in proto-racist terms, that the differences between the peoples would likewise doom this human relationship. He thought that African Americans should be freed – just colonized elsewhere. This is the aspect of Jefferson's thinking that we find so pitiful and depressing, for obvious reasons. Yet we likewise accept to recognize that he was trying to grapple, I recollect sincerely, with a real problem.

No historical account of the origins of American slavery would always satisfy our moral censor today, but as I have repeatedly tried to explain to my Stanford students, the task of thinking historically is non well-nigh making moral judgments about people in the past. That's not hard work if you want to do information technology, but your condemnation, yet justified, volition never explicate why people in the past acted as they did. That's our existent claiming as historians.

-30-

Source: https://news.stanford.edu/press-releases/2020/07/01/meaning-declaratnce-changed-time/

Posted by: jensensuchat.blogspot.com

0 Response to "What Is An Example Of How Thomas Jeffersonã¢â‚¬â„¢s Political Views Changed After He Became President?"

Post a Comment